What happened in South Africa after Nelson Mandela was released from prison

Political prisoner to national reconciler

“It is not always easy to work out how to live a righteous life. That apartheid is wrong is relatively obvious, but how to live against apartheid is the harder question, because even the smallest decision has complicated consequences.” - From Begging to be Black , by Antjie Krog (Random House Struik, 2009).

On 11 February 1990 Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela made his now famous and celebrated walk out of the confines of Victor Verster Prison in Paarl, Western Cape, a walk from the relatively unambiguous position of world-famous political prisoner whom few knew personally, to the highly ambiguous, both emotionally and politically, roles of hero of the nation, leader of the successful revolution, spokesperson for the oppressed and reconciler of the previously warring races.

The day Mandela walked into freedom

It was a Sunday afternoon and we were living, with a number of other people and families, on a small holding in the little town of Halfway House, halfway between Johannesburg and Pretoria. We moved the TV out onto a table in the garden and all sat around it watching this longed-for, hoped-against-hoped-for, event to play itself out on the screen.

We were all still reeling from the events of almost two weeks previously when then President F.W. De Klerk had made his historic opening of Parliament address on 2 February 1990 in which he had announced that all the previously banned liberation movements were immediately unbanned, that political prisoners would be released, and, most importantly, that with regard to the most famous of them, “the Government has taken a firm decision to release Mr Mandela unconditionally.”

De Klerk said on 2 February that, “The Government will take a decision soon on the date of his release. Unfortunately, a further short passage of time is unavoidable.” This, De Klerk said, was because, “In the case of Mr Mandela there are factors in the way of his immediate release, of which his

personal circumstances and safety are not the least. He has not been an ordinary prisoner for quite some time. Because of that, his case requires particular circumspection.”

Since that incredible 2 February Opening of Parliament Address the country and the world had been waiting, anxiously and excitedly, for the moment. It was for us, watching events unfold on the TV screen, almost unbelievably moving. We sat, many of us with tears streaming, until at last we caught sight of the tall, dignified figure in a lounge suit, broad smile creasing the unfamiliar features, hand held high in triumphant greeting to his people, to us. It was, to use a tired phrase for which I can find no better alternative, a defining moment. There was South Africa before 11 February 1990, and South

Link to the Nelson Mandela Foundation

- Nelson Mandela Foundation Home

The Nelson Mandela Foundation contributes to the making of a just society by promoting the vision and work of its Founder and convening dialogue around critical social issues.

Mr. Mandela's Inaugural Address 10 May 1994

- The Inaugural Address speech by Nelson Mandela

Visit this site for the famous Inaugural Address speech by Nelson Mandela. Read this well-known Inaugural Address speech by Nelson Mandela. The Inaugural Address speech by Nelson Mandela is inspiring, motivational and persuasive.

South Africa after 11 February 1990

The South Africa before that date was relatively unambiguous, because you were either against or for apartheid. There were grey areas, of course, there were question marks and, as Antjie Krog wrote, while the question, the moral decision about apartheid was sort of easy – apartheid was wrong, no question, - the bigger question of how to live against it was one which every person had to answer in his or her own way. There were no clear answers and many who could not live with that uncertainty had left South Africa, to join the liberation armies of freedom fighters or for greener pastures in Australia or Canada, where the existential questions were perhaps slightly less agonising and ambiguous.

In the South Africa after 11 February 1990, after the euphoria died down, the realities of the task ahead became more clear, and the difficulties of bringing together people out of the many separate races and classes that had become warring factions under apartheid started to look insurmountable at times.

In the famous 2 February address De Klerk issued an invitation to the leaders of the liberation movements: “Walk through the open door, take your place at the negotiating table together with the Government and other leaders who have important power bases inside and outside of Parliament.”

De Klerk also said, “On the basis of numerous previous statements there is no longer any reasonable excuse for the continuation of violence.”

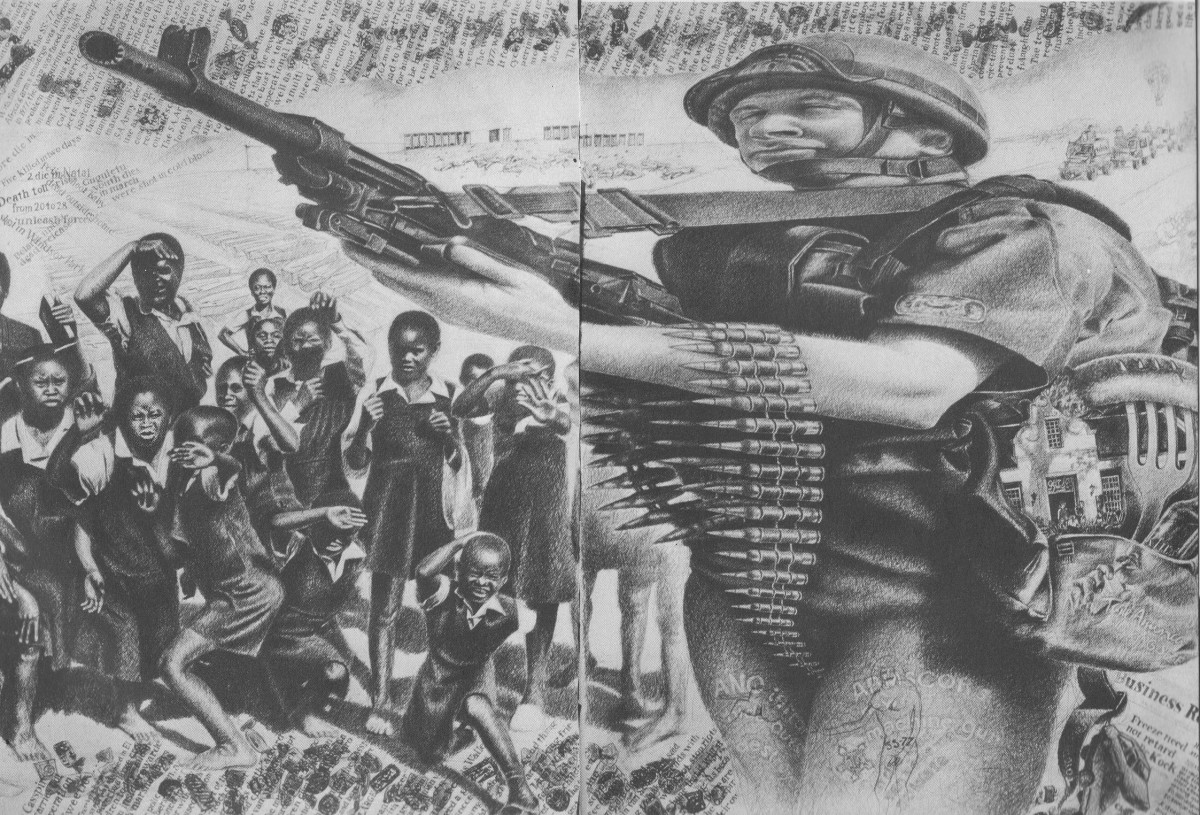

In spite of this the violence increased to incredible levels, with the now-free liberation movements vying violently with the more collaborationist movements that had not been banned, the flames of this violence enthusiastically fanned by some in the shady areas of the security forces and even, perhaps, with the connivance of people up to Cabinet level. There were moments, far too many such moments, when it seemed to us that just when apartheid and its evil machinery was about to be overcome at last, it was threatening to come back in a form worse than before.

It was a time of threats of vengeance, a time of paying back for many. It was not a pleasant time. But it was an exciting time, when, through the dense smoke of the flames, we caught enticing, yet fragile, views of what could emerge, of a better future that could happen.

There was posturing and politicking on both sides, there were accusations and counter-accusations that threatened to derail the whole thing and send us plunging back into the darkness from which we were struggling to emerge.

The Convention for a Democratic South Africa (called, in the absolute flurry of abbreviations and acronyms that came at that time, Codesa) started to meet in a complex of buildings near the Johannesburg airport (then still called Jan Smuts Airport and now called O.R. Tambo International) called the World Trace Centre, since converted into a hotel and casino complex.

Codesa brought together most of the political players and went through many ups and downs, bringing us hope one moment and despair the next.

During the time of Codesa's work many dreadful things took place, each of which threatened to derail the process and plunge the country into a nightmare of violence. These were the Bisho massacre in which 30 ANC supporters were gunned down and killed by troops of the Ciskeian Bantustan government; the Boipatong massacre in which 45 people, mostly women and children, were killed, allegedly by supporters of the Inkatha Freedom Party; the assassination of South African Communist Party General Secretary Chris Hani outside his home on the East Rand; and the invasion of another Bantustan homeland, Bophutatswana, by the right-wing Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging (AWB – the Afrikaner Resistance Movement).

As a priest friend of mine had said to me in the early 1980s, “It is highly unrealistic to expect that 400 years of violent oppression will end without violence.” The violence was frightening, horrible in the extreme, and it was not always clear, through the smoke and rhetoric, who the “good guys” were and who the “bad guys” were.

Codesa continued, in fits and starts, from late 1991 to its collapse as a result of Boipatong, in June 1992.

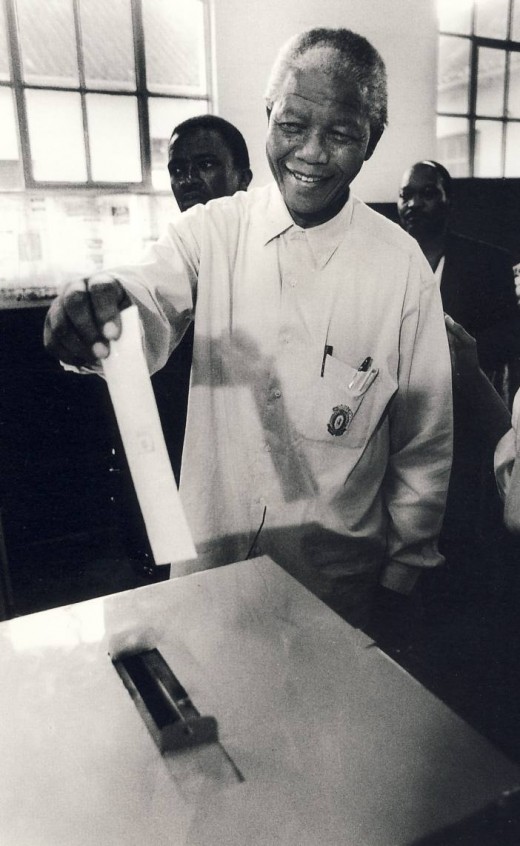

The follow-up was the Multiparty Negotiating Forum (MPNF) which met in April 1993 and was more inclusive than Codesa. The MPNF ratified an interim constitution for South Africa in November 1993 which set up a Transitional Executive Council to run the country until the democratic elections were held on 27 April 1994.

Mandela's legacy

"Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another and suffer the indignity of being the skunk of the world."

- from Nelson Mandela's Inaugural Address, 10 May 1994.

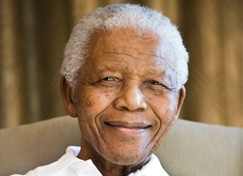

Through all of this the wise leadership of Nelson Mandela helped to steer the country, haltingly and all too slowly, it seemed to us, towards the future which he laid out in his address to the opening session of Codesa: “Our people and the world expect a non-racial, non-sexist democracy to emerge from the negotiations on which we are about to embark.”

When he walked out of that prison on 11 February 1990 Nelson Mandela walked irrevocably into our lives. No-one in South Africa could ignore him any more, no-one could turn the clock back, because Mandela was there as a symbol of what could be, of what was struggling to be born. And is still struggling to be born. The difference now is that we have seen the mountaintop, we know what could be, and will not settle for less. Because the future is now in our hands, all of us, black and white, men and women, rich and poor. We will make that future.