Nongqawuse and the greatest “self-inflicted” national immolation in history?

Apparitions at the mystic pool

One autumn morning in 1856 two young girls went down to a pool dark with overhanging wild banana trees, called Ikhamanga (scientific name Strelitzia nicolai ) by the amaXhosa people, on the river Gxara in the Eastern Province of South Africa. A light mist hung over the pool which added to its feeling of mystery, and the girls were startled by apparitions which seemed to them to rise out of the water and to speak to them words of terrifying import.

The girls ran back to their umzi , homestead, consisting of a few rondavels and a cattle enclosure, to tell the older girl's guardian, her uncle Mhlakaza, what they had seen and heard. Their words were to change the course of history in South Africa, and have left an indelible imprint on the psyche of the amaXhosa, a deep division in Xhosa society, which still exists now, more than 150 years later.

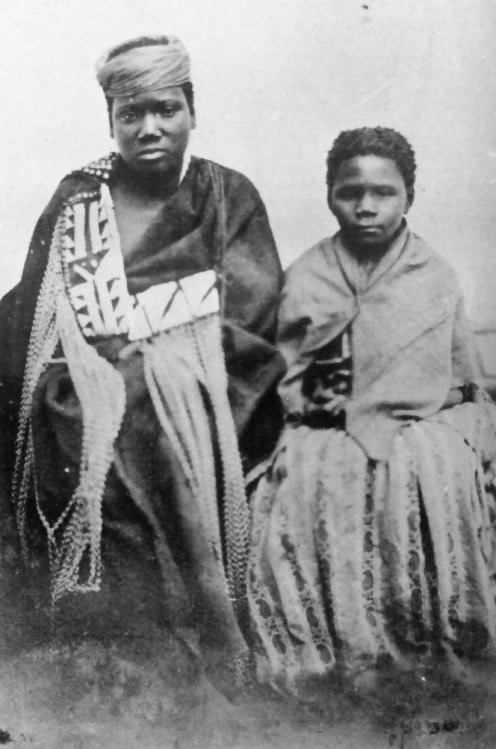

The older girl's name was Nongqawuse, and her companion was Nombanda, related to Mhlakaza by marriage.

The message from the ancestors

The words that the frightened girls heard came to them from two men who identified themselves by name, two names of men long dead, and so men who were “with the ancestors” whose words were therefore of great importance.

The message they brought were that if the amaXhosa fulfilled certain conditions, “new people” would arise and help the amaXhosa sweep the whites and all unbelievers into the sea, the world would be renewed and right relationships restored.

This message, the girls were told, had to be relayed urgently to Mhlakaza and his homestead. In order for this resurrection to occur the amaXhosa had to kill all their cattle, destroy all their crops, build new cattle enclosures for the new cattle they would get and new storage bins dug for all the corn that would be given them.

When they first told this tale to Mhlakaza and his homestead, they were laughed at and scorned, so they tried to forget the whole thing. But the next day they went again to the pool and were again accosted by the apparitions who asked if the message had been delivered. The men repeated the message and added that Mhlakaza should come also to the pool to see them. First, though, he had to sacrifice a beast and ritually cleanse himself before coming to the pool, which he should do four days later.

Mhlakaza did as he was instructed and four days later was at the pool with a group of other men, and Nongqawuse. The men did not see the apparitions but Nongqawuse did and was the medium through whom Mhlakaza spoke to the apparitions.

Mhlakaza asked the apparitions who they were and where they had come from. They said they were the people who had come to order the amaXhosa to kill all their cattle and not to cultivate any crops. When Mhlakaza asked what they should then eat, the apparitions said they would find food for the amaXhosa to eat until the new cattle and new crops would appear. They also ordered Mhlakaza to take this message to the king, Sarili, and all the other Xhosa chiefs.

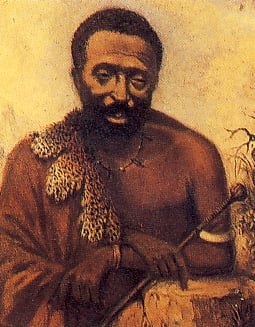

King Sarili was duly informed of the apparitions and their message, was impressed and, after a little hesitation, ordered his people to comply with the demands.

There followed a dreadful time of killing and burning, which lasted several months until the fateful day of 18 February 1857 when the “new people” were expected, when the sun would rise in the east and then turn back to set in the east, and all unbelievers and whites would be swept into the sea. Of course the day dawned like any other day, the sun kept its usual course, and the whites and unbelievers continued on their ways as before.

By now those who had killed their cattle and burned their crops were starving, tens of thousands of them dying, their bodies joining the rotting corpses of their cattle. Many thousands more were helped by the whites and the unbelievers who had not killed their cattle and burned their crops.

Although accurate figures are not available, best estimates are that the amaXhosa in January 1857 numbered, in British Kaffraria, about 105000, a number which dropped to about 37500 in December that year. East of the Kei River the number of dead was estimated at about 40000. Whatever the actual figures, the suffering was immense. Frances Brownlee, a missionary wife in the area, wrote some 20 years later: “Oh! The pity, the heart-breaking grief, the sad horror of it all.”

King Sarili's grandson was interviewed in 1910 by historian George Cory and told him “I sat outside my hut and saw the sun rise, so did all the other people. We waited until midday, yet the sun continued on its course. We still watched until the afternoon and yet it did not turn, and then the people began to despair for they saw that this thing was not true.”

Mhlakaza himself, and his whole family, except for Nongqawuse, died of starvation.

Nongqawuse was arrested by the colonial authorities and taken, largely for her own protection, to Robben Island for a time, after which she went to stay on a farm near Port Elizabeth, where she died in 1898.

The number of cattle killed in this killing frenzy is estimated to be between 300000 and 400000.

The social and political background to the prophecies

To understand the “cattle-killing”, as it has been known by whites, the background scene needs to be set. In the background were two important factors – one political and one veterinary, if you like.

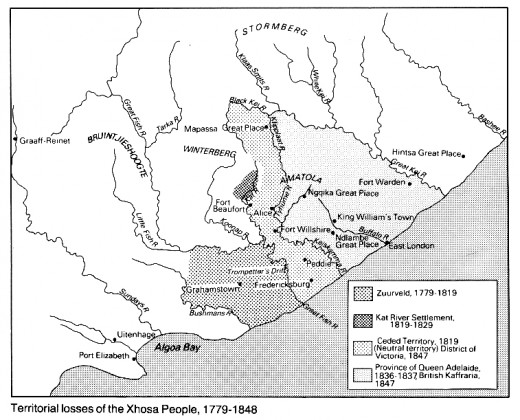

The political factor was the constant encroachment of whites into areas claimed as theirs by the amaXhosa. Apartheid apologists in years gone by (thank God!) used to claim that the white and the amaXhosa arrived at around the same time and found the Eastern Cape to be relatively unoccupied. This was at best a half-truth, as the amaXhosa had in fact been in the area for centuries, though in relatively small numbers. What was true was that they were being pushed in greater numbers further west by the depredations of the expanding amaZulu under their kings Shaka and Cetshwayo. So the amaXhosa were caught between competing expansionist settlers – white to the west and black to the east.

At around the same time the British were involved in the Crimean War in which they lost heavily. The amaXhosa were aware of this and interpreted it as a sign that the British were vulnerable and that the Russians would help them against the British. So messages of people coming to help the amaXhosa had receptive hearers.

The chiefs were divided between collaborationists who wanted to work with the colonialists and the strictly independent chiefs who were determined to maintain their traditional way life at all costs.

King Sarili was in fact the last independent Xhosa king and his rule was shattered by the aftermath of Nongqawuse's prophecies.

The Xhosa resistance to white encroachment was broken by the cattle killing and subsequent starvation of hundreds of thousands of amaXhosa. Those who survived were at the mercy of the colonialists who took full advantage of the situation. There were some instances of resistance after 1858 but they were sporadic and ultimately unsuccessful.

The veterinary factor was introduced to the Cape Colony by the arrival at Mossel Bay of a small herd of Friesian bulls, all carrying the dreaded lung-sickness, or contagious bovine pleuropneumonia, which spread rapidly through the eastern areas of the colony and into the area beyond the Kei River. This deadly disease caused massive stock losses to the amaXhosa, to whom cattle were of great importance. There is a Xhosa saying, “Inkomo luhlanga, zifile luyakufa uhlanga (Cattle are the race, they being dead the race dies)”. This disease which was killing their cattle, and, by extension, themselves, was seen as a supernatural attack on their lives and traditions.

The personalities involved

Nongqawuse was about 16 at the time she went down to the river and came back utterly changed. She was the daughter of Mhlakaza's younger brother who had died some time before. Did she see visions and hear voices, a la Jeanne D'Arc? Was she suffering from some sort of hallucination or was she responding psychologically to the loss of her father and perhaps the emotional aftermath of puberty? We will most likely never know the truth about these things, all we can know is the disastrous effects of what she told her uncle.

Mhlakaza was himself an interesting person in whose background were some mysterious goings on. His name is often spelt Mhalakaza by white writers, but I believe this to be a result of the difficulty English speakers have with the isiXhosa “hl” sound.

Mhlakaza was, some years before these events, an assistant to Nathaniel James Merriman, at the time Archdeacon of Grahamstown. Merriman, whose son John Xavier was later to become Prime Minister of the self-governing Cape of Good Hope, undertook extensive travels throughout the Eastern Cape, finding out about the people of his rather large parish. In this work he was assisted by an isiXhosa speaking man who called himself Wilhelm Goliat, but was in fact Mhlakaza.

Mhlakaza had been in contact with Methodist and other protestant missionaries, but this was his first contact with the more catholic rituals of the Anglican Church, with which he was very impressed. In fact he became the first umXhosa to be confirmed in the Anglican Church. He only left Merriman when Merriman's wife insulted him in some way.

Mhlakaza seems to have woven a rich tapestry of belief incorporating the tradition world view and religion of the amaXhosa with the rituals and teachings of the Anglican Church. He was in his own right a traditional healer, or, as whites of the time would have called him, a “witch doctor.” So the world of the spirits was a daily reality to him, as it was actually to most of his people.

The Xhosa belief about their origins is described by Noel Mostert in his excellent book Frontiers (Pimlico, 1993) thusly: “It was from still waters, a place of reeds, wind-stirred grasses and wild fruits and flowers that the human ancestors first emerged...” Certainly that mystic pool on the Gxara River was such a place.

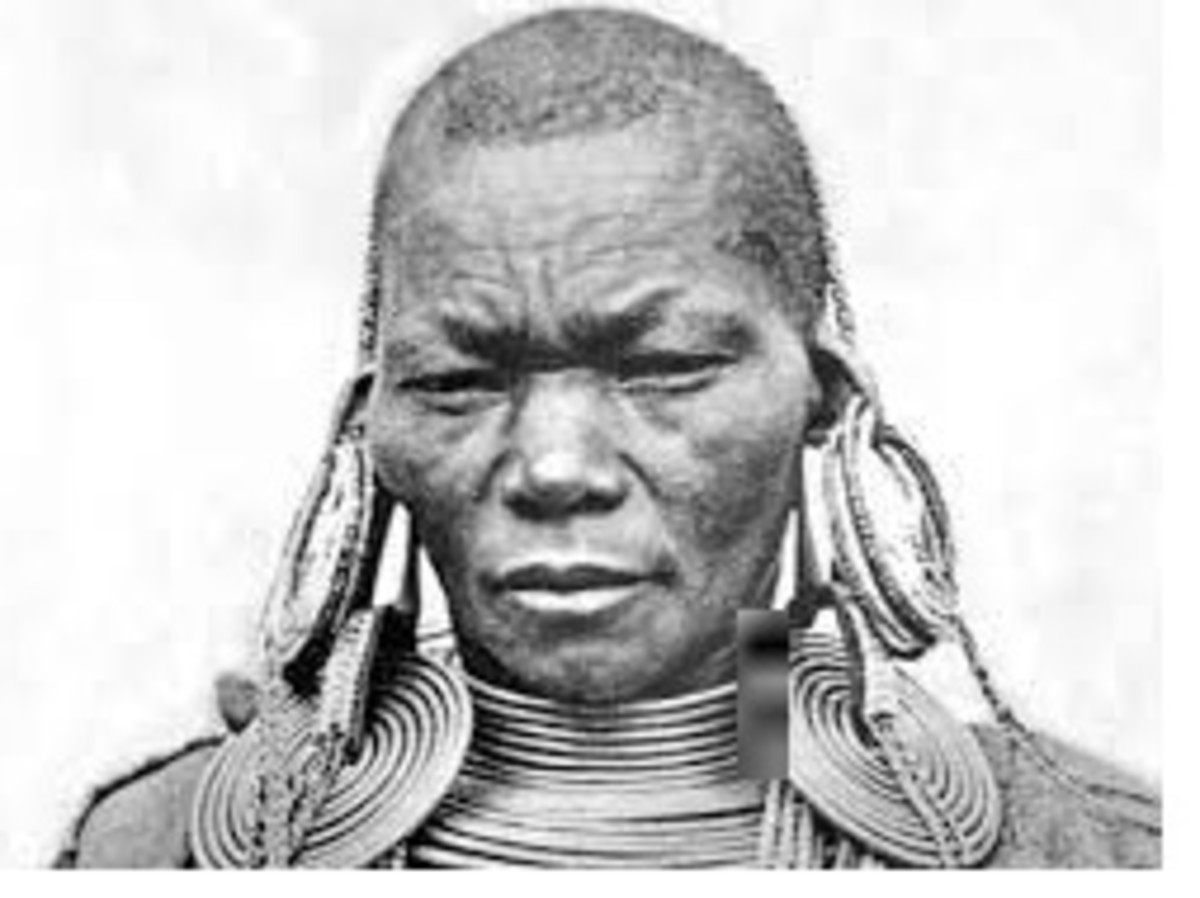

The longer-term results of the slaughter

At the time of Nongqawuse's prophecies the people tended to either believe fully or disbelieve fully. The prophecies therefore drove a deep divide into Xhosa society, between the believers, called the amakholwa , and the unbelievers, called the amaqaba (literally the “smeared ones). These divisions persist today, overlayed by Christian / non-Christian overtones. The unbelievers are also called by whites “red” people because they continue to smear red ochre on their bodies and wore red-dyed blankets, while the amakholwa are known as “white” because they wore white blankets. The divide is also expressed in isiXhosa as abantu ababomvu (the red people) or abantu basesikolweni (the school people).

These events destroyed any hopes the amaXhosa might have had of retaining their independence. The resulting divide continues to haunt the amaXhosa, to most of whom these events are still the cause of deep shame.

Who was really to blame?

There is an old question much used by the Roman orator Cicero, “cui bono?” I think it is applicable here. To whose advantage was the slaughter? And there can be absolutely no doubt about the answer to that question.

The white settlers were immeasurable helped by the slaughter, they benefited in many, many ways.

The need for farm labour, since slavery had been stopped some 40 years before, was dire. The need for more land to grace their stock and to cultivate their crops was urgent.

The British Government needed land to settle people who could no longer make their livings in Britain, or to reward soldiers who had fought on their side in many different wars.

The colonial authorities needed to stamp their authority on the eastern boundaries of the colony in the most cost effective ways.

In my mind there is little room for doubt that the whole thing was engineered by whites. The question that is left is how did they do it? Who were the people who spoke to Nongqawuse at the pool? Who told them to say what they said?

These are all imponderables and there can likely be no certain answers. There is no doubt however that large sections of settler society welcomed the tragedy. Settler opinion was firmly against assisting the survivors, who were to be allowed to die. Some among the missionary societies were appalled and deeply moved by the tragedy, but I also have some niggling questions about the roles of the missionaries themselves. To what extent did Merriman, for instance, influence Mhlakaza? What ideas did he put into the mind of the traditional healer?

Whatever the answers to these questions, the reality remains that the cattle slaughter of 1856 and 1857 still casts a shadow over the Eastern Cape and the people living there. As W.B. Yeats would write some 60 years later, “All changed, changed utterly” but the next line of his poem does not apply, for there was no “terrible beauty” born out of the suffering of those people, no beauty at all.

Further reading

For further reading on these fascinating and terrible times the best overall understanding of the challenges facing Xhosa society and the history of the contact between whites and blacks in the Cape Colony comes from Noel Mostert's magisterial Frontiers , but a more novelistic insight can be had from Zakes Mda's superb novel The Heart of Redness (OUP 2000), in which these events play an important role.

An excellent general introduction to South African history is the book edited by Trewhella Cameron: An Illustrated History of South Africa (Jonathon Ball Publishers, 1986).

The immediate inspiration for this Hub came about from a re-reading of the beautiful book African Elegance written by Joan Broster with photographs by Alice Mertens (Purnell, 1973). In particular the gorgeous photo reproduced above of the “modern Nongqawuse” got me thinking about these events again.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2009