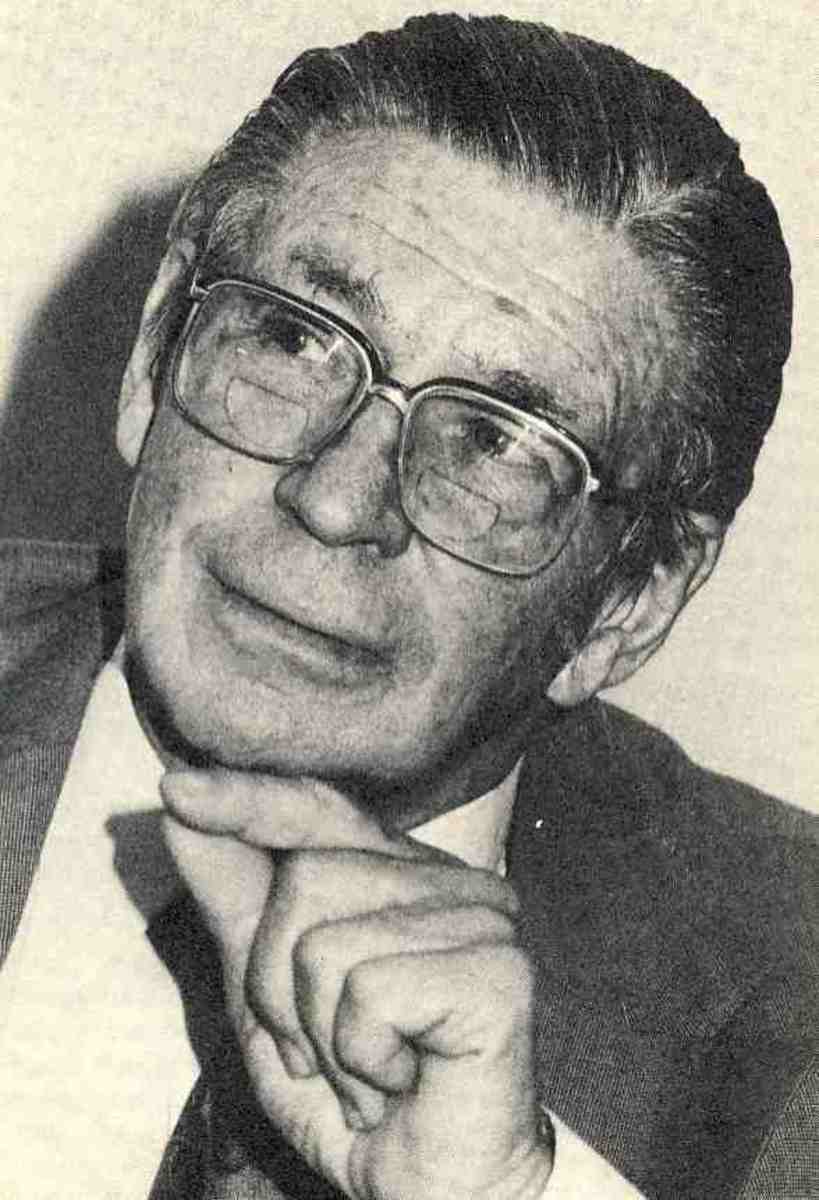

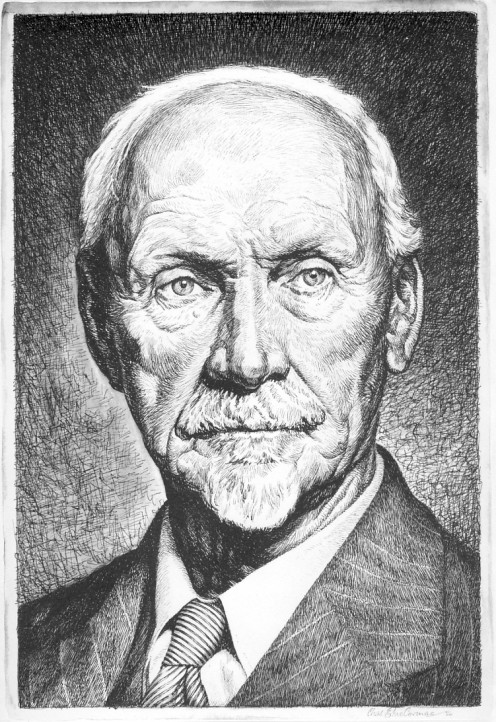

Jan Christian Smuts – enigmas and contradictions writ large: Part 1

Humble birth

On 24 May 1870 a man was born in humble circumstances near a little hamlet in the Cape Colony (now the Western Cape Province of South Africa) called Riebeeck West, who in later life was to hob-nob with Kings and Presidents, scientists and soldiers, philosophers and politicians, nobles and peasants, from around the world.

The brilliance and potential of Jan Smuts was recognised by Cecil John Rhodes and Paul Kruger; he fought against the British in the Boer War and came to be seen as a devoted friend of Britain in two subsequent World Wars.

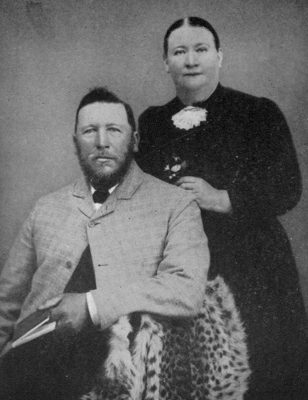

Jan Christian (often familiarly called “Jannie”) Smuts was the second child of Jacobus and Catharina Smuts of the farm Bovenplaats in the Malmesbury district where he grew to the age of 12 before getting any formal education, and that only after his older brother, Michiel, died in 1882.

Education and love

He was in his very young days a thin, frail child with piercing blue eyes and a reserved, shy and rather silent nature. But at the boarding school to which he was sent he was soon recognised as an outstanding pupil, and he decided to go to Victoria College in Stellenbosch (the forerunner of the University of Stellenbosch).

To gain entrance to the College he had to pass a matriculation examination, including a paper in ancient Greek, which he had not yet been taught due to his late start at school. He set himself the task of learning the Greek needed for the exam and in six days, without a teacher, he not only passed the exam but was top of the list of candidates in that subject.

While at Victoria College two things happened to the shy, stiff young man (he was just 17). First he discovered love, in the form of Miss Sibylla Margaretha Krige, known affectionately as Isie, daughter of a local man, Japie Krige, who was strongly anti-English, as so many Afrikaners were at the time. He would write of her in his diary, some years later: “(She being).. less idealistic than I, but more human, recalled me from my intellectual isolation and made me return to my fellows. Second, his studies of the English Romantic poets and of Walt Whitman, led him to re-assess the stolid Christianity he had inherited from his family. He began to question and to search for answers, and, given his nature, would do so doggedly, until satisfied that he had everything necessary to understand.

This second aspect of his time at Victoria College led him to change his mind from studying to become a pastor, towards studying the law.

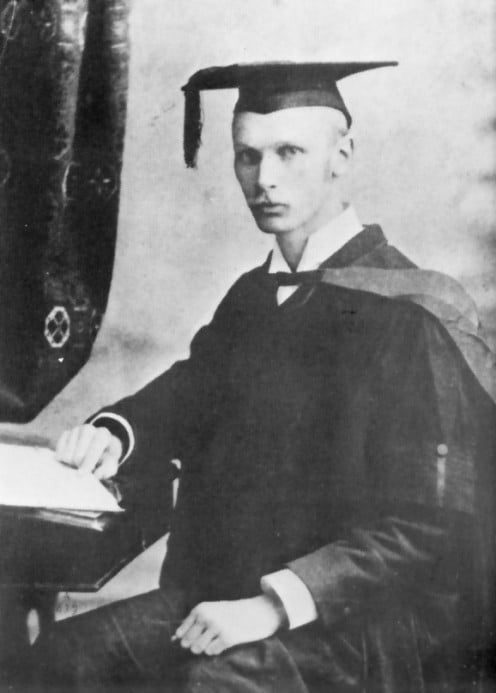

In 1891 he took a double-first in literature and science, and then applied for the Ebden Scholarship which was offered by the University of the Cape of Good Hope. He won the scholarship and duly left for Cambridge in September 1891 aboard the Roslyn Castle.

His time at Christ's College, Cambridge, where he studied law, was marked by outstanding academic achievements and a broadening of his interests into areas such as botany (in which he would later make some useful contributions), archaeology, philosophy and poetry.

While at Christ's College Smuts was deeply impressed by the poetry of Walt Whitman and even found the time to write a book about him, entitled Walt Whitman: A Study in the Evolution of Personality. The book was published until 1973, when it was put out by Wayne State University Press.

In December 1894 he sat for the examinations of the Inns of Court, passing them at the head of the list, and was called to the Middle Temple. His college, Christ's, offered him a fellowship in law, but he preferred to return to South Africa, which he did in 1895.

Back in South Africa

He was called to the Cape Bar and went into practice as a barrister, but was not particularly successful. He took on some writing work for the Cape Times, especially reporting on the Cape Parliament. This aroused his interest in politics, an interest that would be with him for the rest of his life.

Smuts soon came to the attention of the Cape Premier, Cecil John Rhodes, who hired Smuts as his personal legal advisor.

Smuts was soon overwhelmed by the Rhodes charisma and vision, defending Rhodes against attacks from Afrikaners who saw in Rhodes's imperial ambitions a threat to their own independence. In October 1895 Smuts made a long and impassioned speech in support of Rhodes, earning sharp criticism from many quarters as a result. Smuts was not moved by the criticism.

What did move him was his “betrayal” by Rhodes who at the end of 1895 had connived at and funded the raid into Kruger's Zuid Afrikaansche Republiek (ZAR) by forces under the command of Leander Starr Jameson, the infamous Jameson Raid, which was the spark to the tinder of Anglo-Boer relations. Smuts was absolutely devastated by the news of the raid. He had placed much hope on his relationship with Rhodes, hope that his careers in the law and politics would soar with Rhodes's backing had turned to dust. Rhodes, who had personally predicted great things for him, had let Smuts down in the worst possible way – Rhodes had done precisely what Smuts had with such passion said he would not do, plot against the ZAR and Afrikaners generally.

Smuts packed up his chambers in Cape Town and decamped to Johannesburg, the dusty, bustling centre of the burgeoning gold mining industry, in August 1896.

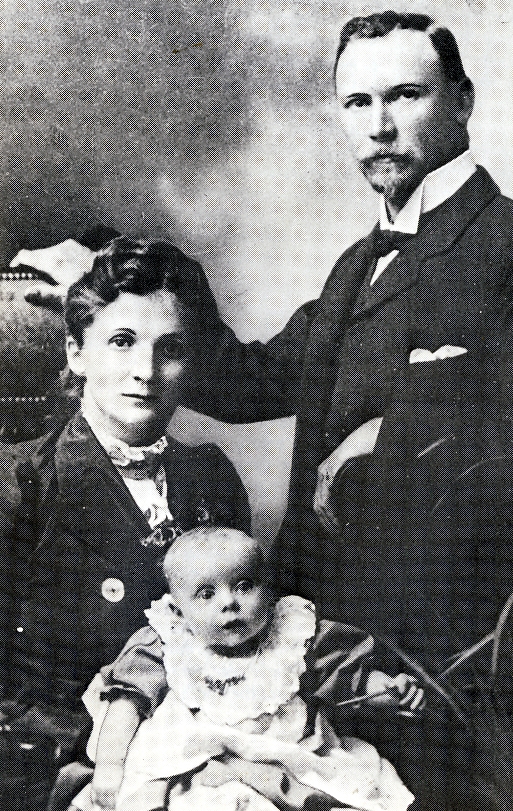

In April 1897 he married Isie Krige and they settled together in Johannesburg. Neither of them liked the overgrown mining camp and Smuts's law firm was not prospering when in June 1898 Kruger in his often autocratic way fired the Chief Justice of the ZAR, John Gilbert Kotzé, because of an unfavourable judgement. Smuts took it upon himself to write a legal opinion in favour of Kruger, who had been heavily criticised in legal circle for his action.

Kruger was already aware of the brilliant young legal mind from the Cape and on 28 June Smuts was given second-class citizenship of the ZAR and on the same day Kruger appointed him State Attorney.

Smuts had achieved an amazing turnaround - from enthusiastic supporter of Rhodes and the imperial vision to becoming the right-hand man of Rhodes's implacable enemy and ardent opponent of the imperial dream, Kruger.

The Anglo-Boer War

When this war broke out in October 1899 Smuts was at first kept in Pretoria as Kruger's right hand man, applying his considerable energy to organising the Boer war effort on several fronts, including the diplomatic one.

Eventually, when Pretoria fell to the British forces in June 1900 the ZAR government was transferred to Machadodorp in the then Eastern Transvaal, now Mpumalanga Province, and Smuts raised an army of 400 to 500 men and rode off to conduct guerrilla raids on British supply columns.

Smuts rode into battle with Kant's Critique of Pure Reason (probably in the original German) and a Greek New Testament in his saddle-bag. This is an early evidence of the strange disconnect between his high intellectual leanings and the almost crude practical actions of the man: the commando which he led was responsible for the massacre in 1901 of some 100 blacks at the mission station of Modderfontein, not the last time his name would be associated with a massacre of blacks. Canon Farmer, the missionary at Modderfontein, wrote, “I should be sorry to say anything that is unfair about the Boers. They look upon the Kaffirs (sic) as dogs & the killing of them as hardly a crime ...”

The enigma of how a person with such a broad mind and depth of culture can participate in such brutality is an enduring issue.

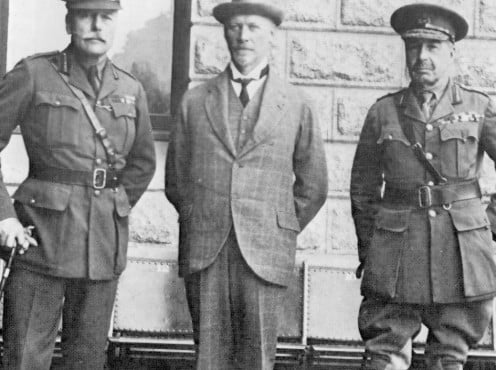

When the Boers in March-April 1902 realised that continuing the fight was no longer worth the cost in death and destruction, Smuts was one of the six-man delegation that set out by train for Pretoria and negotiations with Milner in Melrose House.

Smuts took a leading role for the Boer side in these negotiations, even to the extent of having a private chat with Milner, the High Commissioner, and Kitchener, the Commander of the British forces. The three drew up a preamble to a peace agreement but this was later rejected by General De Wet on behalf of the president of the Orange Free State.

Smuts and the Attorney General of the Cape, Sir Richard Solomon, together with J.B.M Hertzog and Milner, then drafted the agreement which was finally signed at Melrose House.

Peace to Union

No sooner had the dust and smoke of war started to settle and Smuts was involved in politics again. He helped draft a new constitution for the Transvaal Colony, as the ZAR had now become, and in the elections of 1906 won the Wonderboom seat. He was almost immediately invited into the Cabinet formed by his war-time comrade General Louis Botha and given the portfolios of Colonial Secretary and Education Secretary.

As Colonial Secretary he had to negotiate with the leader of the Indian community, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Smuts was, however, still strongly in favour of a united South Africa and pushed hard for the formation of the National Convention to work out the process of unification and the shape of a future union of the four colonies in South Africa.

The National Convention sat from October 1908 to the early part of 1909, when all the delegates accepted Smuts's draft constitution. Smuts and Botha then travelled to London to present the draft to the British Parliament, which ratified the constitution quickly, and the Union of South Africa came into being on 31 May 1910, eight years to the day after the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging.

Louis Botha was appointed Prime Minister and Smuts his deputy.

Problems in the young union

n 1913 this government passed the infamous Natives' Land Act which effectively restricted ownership of land by blacks to about 7% of the land in the country, the balance being open for ownership by whites only. The foundation of territorial segregation was laid.

Also in 1913 occurred one of those instances which showed the ruthless side of Smuts, the “Grey Steel” (Grey Steel is the title of a 1939 biography of Smuts by H.C. Armstrong) man who would seemingly without compunction deal death to opponents.

A mine management decision to cap wages of less skilled workers led to a strike which quickly turned violent. This needs to be seen against the background of what was termed back then the “poor white” problem.

As a result of the large scale and widespread destruction of Boer farms (according to one estimate about 30000 farmsteads were destroyed, and about 20 villages) during the Boer War thousands of Afrikaners were left destitute, with few skills that were relevant in the rapidly-modernising South African economy. They migrated in large numbers to the growing industrial towns of the Witwatersrand where they tended to congregate in shack settlements.

Parliament appointed a Select Committee on European Employment and Labour Conditions which reported that “These are people who have sunk into a demoralising and corrupting intercourse with non-Europeans with evil effects on both sections of the population.”

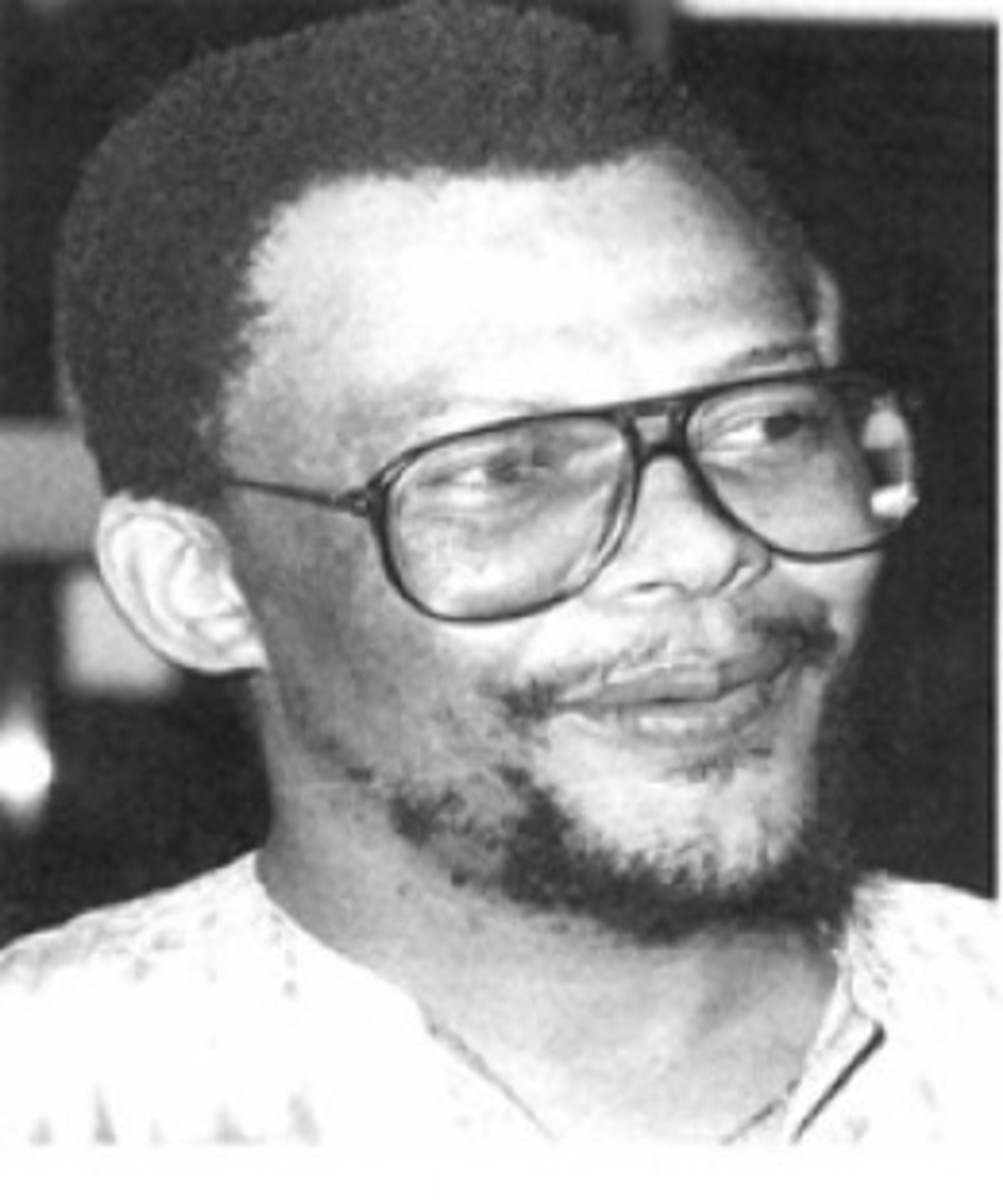

As Robert Davies (incidentally, he is now the Minister of Trade and Industry in the Cabinet of President Jacob Zuma) wrote in his book Capital, State and White Labour in South Africa 1900 – 1960 (The Harvester Press, 1979): “... in some cases unemployed whites and Africans lived together in the same shanties, and there were even cases of whites begging food from Africans, or performing odd jobs for Africans in return for food and shelter.”

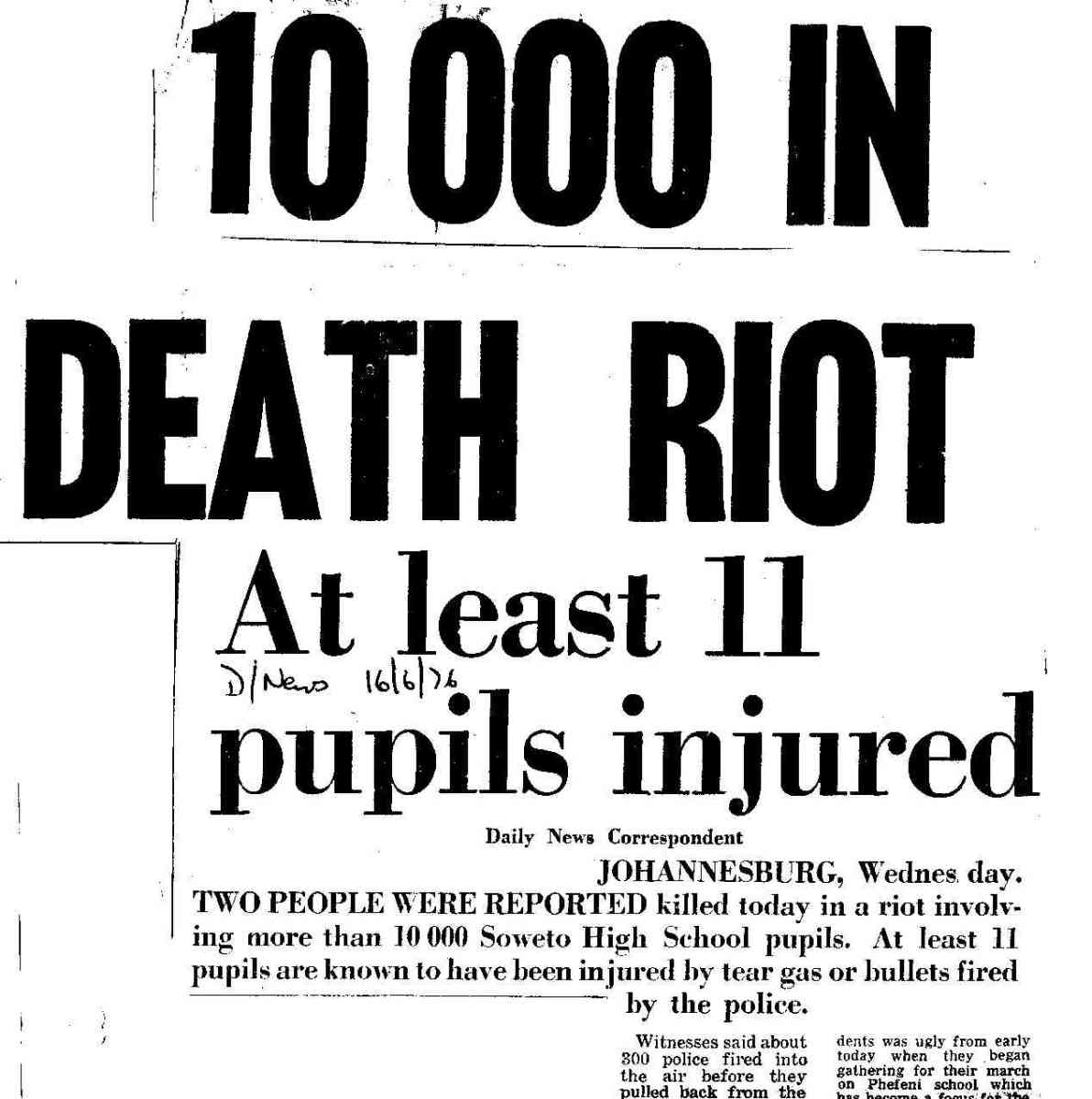

On 14 July 1913 a mass meeting of white mine workers was organised for which Smuts at the last minute refused permission. The meeting went ahead anyway and afterwards a large crowd gathered outside of the Rand Club in Johannesburg, the favourite gathering place of the mining magnates.

Smuts, as Minister of Defence, sent in troops to control the strikers who had turned violent. The strikers refused to disperse when ordered to do so by the police, who then opened fire, killing 51 strikers.

When the government nationalised the railways in early 1914 a general strike was called, to which Smuts responded by deporting, totally without legal sanction, nine of the leaders. He simply had them taken from the cells where they were being held, taken to Durban where they were put aboard the steamship Umgeni, bound for London.

At least in part the reaction of Smuts and the ruling party can be explained by their perception of the growing relationship between the “poor whites” and the blacks, a relationship which was seen as, in Davies' words, “a factor undermining the efficacy of the ideology of racism as a means of exerting social control over Africans.”

In a speech in London in 1917, when Smuts was a member of the Imperial War Cabinet, he revealed the underlying racism of his outlook: “Natives [this was the term used generally by whites for blacks at the time] have the simplest minds, understand only the simplest ideas or ideals, and are almost animal-like in the simplicity of their minds and ways.”

Later in the speech he was to say, “To apply the same institutions on an equal basis to white and black alike does not lead to the best results, and so a practice has grown up in South Africa of creating parallel institutions — giving the natives their own separate institutions on parallel lines with institutions for whites.”

This from the same mind which would later produce a passage in his monumental book Holism and Evolution (first edition 1924; now published by N & S Press, 1987): "For we are indeed one with Nature; her genetic fibres run through all our being; our physical organs connect us with millions of years of her history; our minds are full of immemorial paths of pre-human experience. Our ear for music, our eye for art carry us back to the early beginnings of animal life on this globe."

One of the enigmas of Jan Smuts!

After World War I

In 1914 when Botha, in support of the British war effort, invaded German West Africa (now Namibia) the decision was bitterly opposed by many of the old Boer generals and their followers.

One member of the South African Defence Force, who had previously fought on the Boer side in the Boer War, Jopie Fourie, joined in a rebellion against the South African Government. He was captured near Rustenburg in the then western Transvaal (now part of North west Province) on 16 December 1914, court martialled and executed by firing squad on 20 December. He instantly achieved martyr status among Afrikaners of the anti-Smuts camp.

At the end of the “War to end all wars” in 1918 Smuts attended the Peace Conference in Paris, where he argued strenuously, though unsuccessfully, for a less punitive settlement with Germany, arguing presciently that the terms eventually forced on Germany would breed resentment and hatred and would be destructive of peace.

When Botha died in 1919 Smuts became Prime Minister and was very soon embroiled in conflict again.

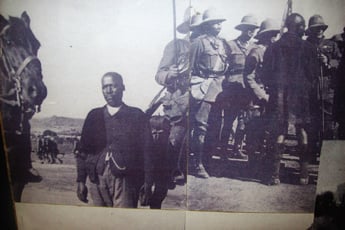

The first conflict arose out of a prophecy of the end of the world made towards the end of 1919 by a preacher in the Eastern Cape, Enoch Mgijima. Mgijima told his numerous followers that the world would end in 1920 and that they should go to a place called Ntabelanga, near Bullhoek in the district of Queenstown.

About 3000 of his followers squatted there on government land without permission and refused to budge in spite of efforts by local officials to negotiate with them. Evnetually a small army of 993 policement and 35 officer was assembled at Queenstown and on 24 May 1921 the 500 followers of Mgijima, called “Israelites”, were surrounded and the order was given to shoot. The Israelites, being armed only with sticks and knobkieries, were mowed down. About 163 were killed, 129 wounded and 113 taken prisoner.

This incident has ever since been known as the "Bullhoek Massacre" and blame for it is usually laid at the feet of Smuts.

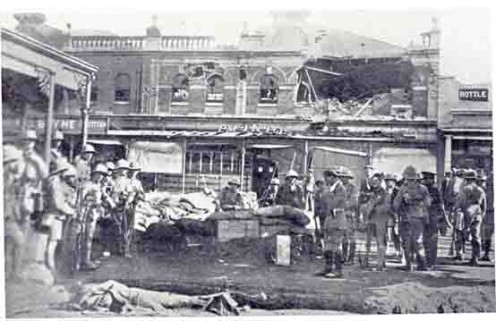

The following year another conflict between miners and the mine magnates began, again precipitated by the latter's decision in January 1922 to reduce the wages of miners.

Smuts tried to negotiate but the miners, remembering 1913 and 1914, did not trust him at all. Smuts then decided that the Government should remain neutral in the struggle: "The Government will remain severely impartial. We will make a ring round you disputants and let you fight it out."

The Union Federation representing the miners then began to set up a militia, convinced that the opposition party in Parliament, led by former Boer General J.B.M. Hertzog would come to their aid.

The Federation asked for a round table conference to discuss the issue as miners all over the Witwatersrand began to agitate, refusing to work. The answer of the Chamber of Mines was rough: "We will waste no more time . .. trying to convince people of your mental calibre and we see no reason why we should discuss our business with representatives of slaughtermen and tramwaymen."

The revolt spread and Johannesburg was in a panic. Smuts came poste haste from Cape Town ad took charge of the situation. He ordered the army to attack and for planes to bomb rebel positions.

The rebellion was smashed and about 200 miners were killed. It was typical Smuts strong-arm tactics and it cost him the election of 1924.

Once he was no longer the Prime Minister Smuts set about writing the book that had been germinating in his mind for some time – Holism and Evolution, - dealing with “some of the problems which fall within the debateable borderland between Science and Philosophy.”

Part 2 ...

Smuts looms very large over South African history, from the Boer War to the aftermath of the Second World War.

In this first part I have covered his enigmatic life up to the end of his first stint as Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, a country whose character he had a major role in shaping.

In Part 2 I write about his emergence onto the world stage during the Second World War and his defeat in the 1948 elections.

Copyright Notice

The text and all images on this page, unless otherwise indicated, are by Tony McGregor who hereby asserts his copyright on the material. Should you wish to use any of the text or images feel free to do so with proper attribution and, if possible, a link back to this page. Thank you.

© Tony McGregor 2011